Surgical site infections (SSIs), the most frequent type of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), are known to occur up to 30 days after surgery and affect either the incision or deep tissue at the operation site.

Infection during surgery

Approximately 10 percent of patients who have surgery in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) acquire SSIs. [1], [2] This undesirable effect can be a significant clinical problem, as SSIs dramatically increase the direct and indirect cost of treatment and reduce the health-related quality of life. [2] Numerous patient-related and procedure-related factors are known to influence the risk of SSIs.

The role of reusable surgical instruments

Reusable surgical instruments represent one potential route for the transmission of pathogens, as they are contaminated with blood and microorganisms to varying degrees after every operation. [3] Guidelines recommend that reusable surgical instruments should be sterilized between uses. [4], [5], [6] Therefore, from use to reuse these instruments go through a complex decontamination journey; a vital component in the prevention of HAIs. This reprocessing of medical instruments involves transfer, pre-cleaning and decontamination, preparation and maintenance, packaging, sterilization, and storage until the moment of use. [4], [5]

Challenges during / After sterilization

Methods of instrument sterilization include steam and low temperature sterilization. During the process the instruments can either be wrapped in sterilization wrap or placed into rigid containers. [7] A considerable number of instrument sets are wrapped. However, if wraps are damaged by the instruments or trays they are holding, the sterilization process needs to be repeated. On average, 5 percent of wrapped instrument sets are reprocessed due to tears. [8] Damaged sterile packages or wet sets might cause operating room downtimes and time pressure. Moreover, holes in wraps might appear without discrimination and might be overlooked. In that case they represent a serious risk factor for SSIs.

Detection of holes in the sterilization packaging

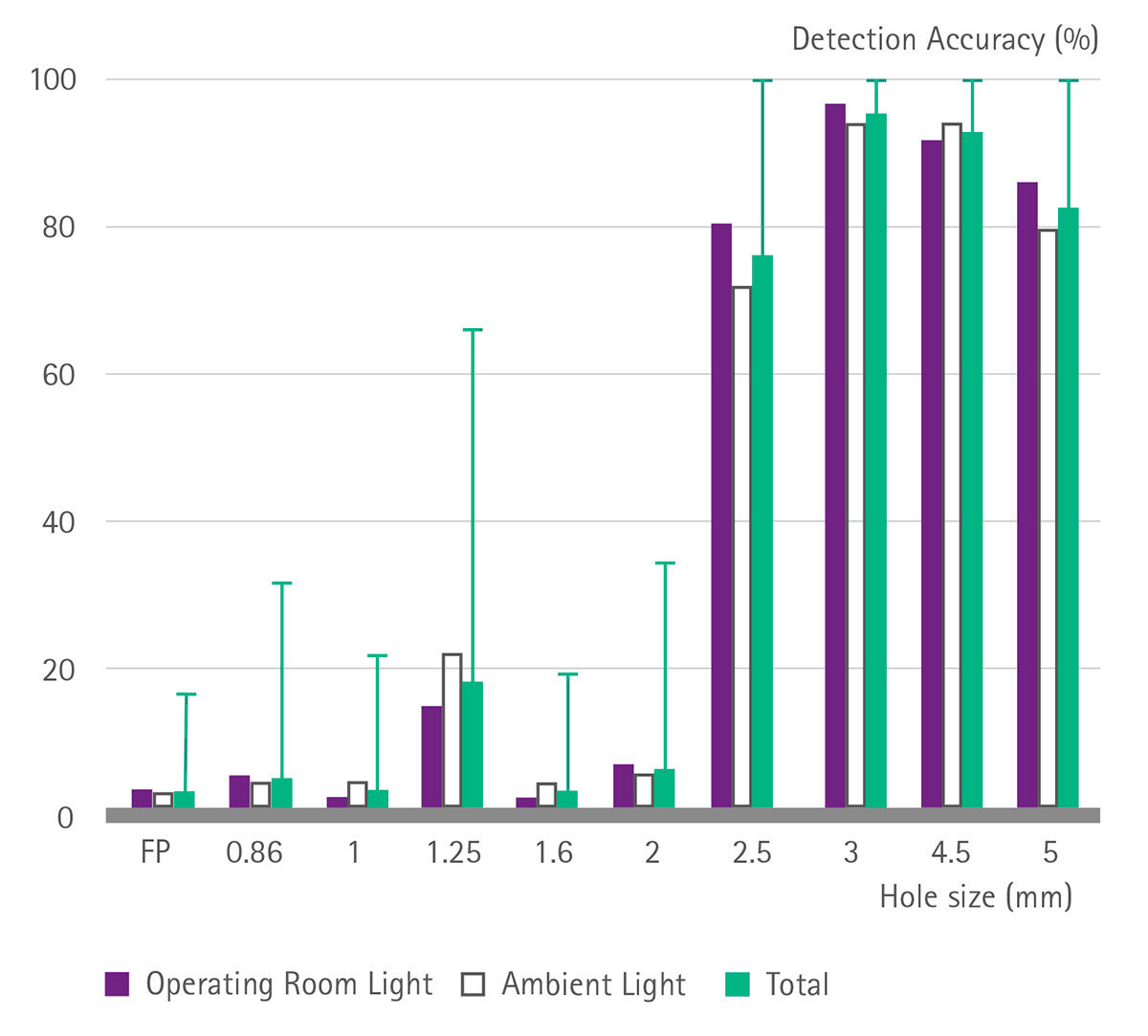

There appears to be difficulty detecting holes in sterile wrappings that are less than 2 mm in size. As Waked et al. found out in a 2007 survey, defects with a diameter of 6.7 mm were missed 18 percent of the time. At the same time they could prove that puncture holes as small as 1.1 mm could transmit contaminates through the wrapping material. [9] In 2018, Rashidifard et al. repeated the analysis with a larger sample size and under various conditions. [10] The study included 30 surgical personnel from two different hospitals and was comprised of surgical technicians, operating room nurses, and orthopedic surgery residents. 9 different defect sizes between 0.86 mm and 5.0 mm were pierced into completely sterile wraps using different tools. Sterile wrap inspection was conducted by unwrapping the sterile dressing, lifting it to a light source in the operating room, and identifying any perforations that may compromise sterility. The study group corroborated the results from 2007; holes with a diameter of 2.5 mm were detected more often than holes with a diameter of 2 mm.

Figure 1: Detection percentage rates for each hole size (mm) under different conditions.

Figure 1: Detection percentage rates for each hole size (mm) under different conditions.